Investing is personal. Behind data and numbers are emotion and feelings. It’s one thing to read The Great Crash, it’s another thing entirely to read The Great Depression: A Diary. One provides the macro- how much stocks fell and how high unemployment got- the other provides the micro, the human element. Here’s Benjamin Roth writing in his diary in 1931.

Magazines and newspapers are full of articles telling people to buy stocks, real estate etc. at present bargain prices. They say that times are sure to get better and that many big fortunes have been built this way. The trouble is that nobody has any more. On account of numerous bank failures, the few people who have money are afraid to spend it and are buying government securities. From the extreme of speculation in 1929 people have now turned to the extreme of caution. In my own case I find it a problem to take in enough to pay and there is nothing left for investment.

It would take twenty-five years before the Dow reclaimed its 1929 peak. Over that time the United States had four different Presidents and we built the Hoover Dam, the Empire State Building and the Golden Gate Bridge. The Hindenburg exploded, the F.B.I was established, the atomic bomb was dropped, Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier, and the world experienced its second great war. It only takes a minute to look this up, but these events actually played out over thirteen million minutes. This is why I like to say that history gets lost in the charts.

We all play on the same field, but each of us run different routes. Meir Statman talks about this in his new book, Finance for Normal People.

“The utilitarian benefit of two investments are identical when they yield an identical return, but the satisfaction they yield, reflecting expressive and emotional benefits, varies by the paths of identical returns.”

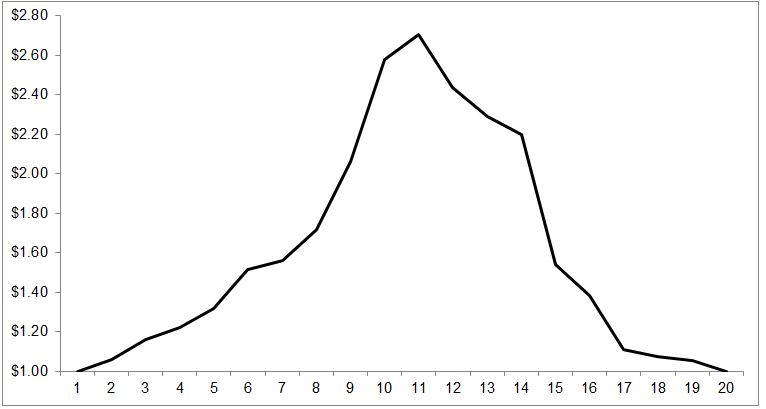

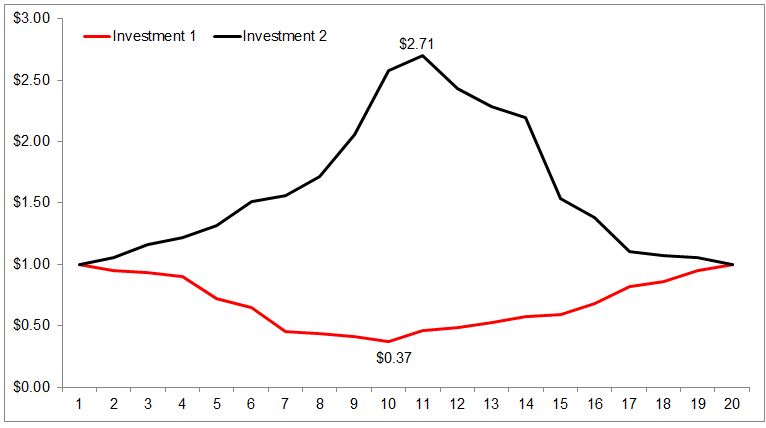

Let’s look at two hypothetical investments to make the case that actual returns and emotional returns are not one and the same. Investment one starts out bad and then gets worse. Over the first nine periods, a dollar compounds at -10.5% a year. Each dollar invested falls to $0.37. But the investment and investor in this case perseveres; it scrapes and claws its way back to even.

The second investment is a mirror image. One dollar compounds at 10.5% over the first ten periods and at one point it’s up 171%. But all the gains in the first half would be ripped away in the second half.

The two investments experienced identical returns, but the investor experience could not be more dissimilar.

The first investment would make me feel like Jim Simons. Even though the actual return was zero, the satisfaction yield would be off the charts. There’s nothing like the feeling of breaking even. The second investment on the other hand would make me sick. I wouldn’t think of it as house money. To me that would feel very much like a real loss. If I was up 171% and gave it all back, my hindsight bias would be kicking into overdrive.

The fact that the return of principal under different scenarios can evoke such different emotions tells us a lot about why investor behavior is the most important factor in determining success or failure.

I’m extremely excited to see Meir Statman speak at the Evidence-Based Conference (West) in a few weeks. The whole lineup is killer.