With a 44% gain, Bitcoin is far and away the best performing asset so far in 2020.

What this means, exactly, is that if you bought Bitcoin on December 31st at precisely $7,119.63 and held it until today, the value of your coins have increased by 44%. El capitan obvious, I know, but this is important because the way we talk about returns matters.

Bitcoin is up 44% over the first 42 days of the year, that’s a fact, but another fact is that Bitcoin started the year 64% below its all-time high, and still remains 48% below those levels. This got me thinking, what if stocks followed the same sequence of returns as Bitcoin since its peak in 2017. What would the headlines be like?

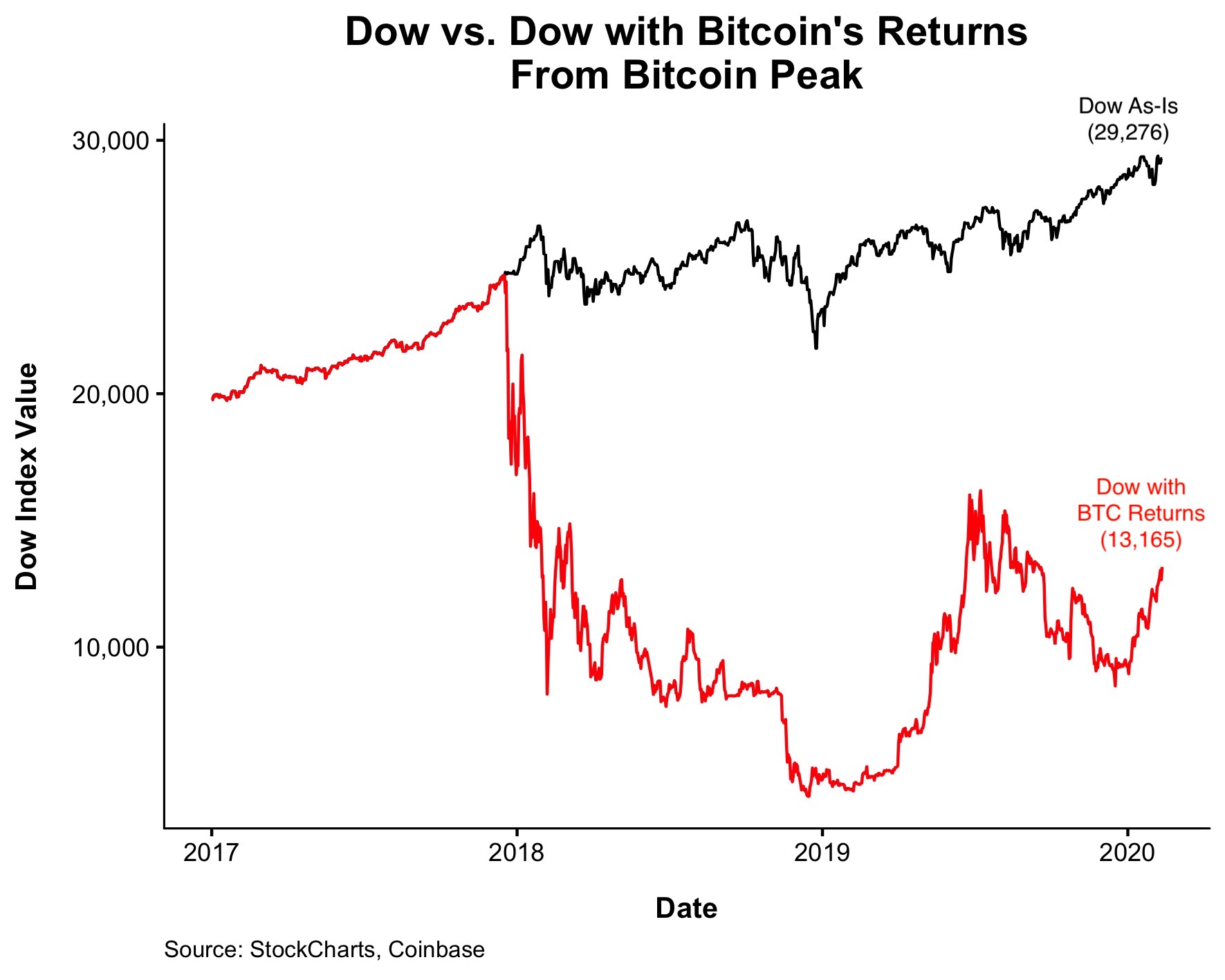

As Bitcoin made its final high in December 2017, the Dow was also making all-time highs. The chart below, which is absolutely of the criminal variety (Nick is an accomplice), shows that if the Dow had followed Bitcoin’s path, it would be at 13,165 today (up 44% YTD and 48% below its ATH).

If this actually happened, the headlines would not be “Dow up 44% YTD,” they would be more like “Dead cat bounce?”, “Too far too fast?”, and things far more incendiary.

I’ll be the first to admit that comparing the Dow to a nascent asset like Bitcoin is silly, I only point this out to show the absurd yet inevitable way in which we view performance.

We frame returns in terms of where something is today versus the high, versus the low, versus the beginning of the year, and versus the last 1, 3 and 5 years, to name a few. And all of these are valid to varying degrees, but nothing frames your view on an investment like the price you paid for it.

Viewing the world through this lens can lead to all sorts of behavioral mistakes, which I’ve committed more times than I’d care to admit.

The thing that’s especially troublesome about our brains on stocks is that being aware of our own foibles does not give us the ability to overcome them. It’s almost impossible to break free from the shackles of how an investment has treated you. Objectively analyzing something on its own merits instead of your P&L is what separates the wheat from the chaff.

I’ll give the last word “Adam Smith” who wrote about this in The Money Game, one of my favorite investing books ever.

A stock is for all practical purposes, a piece of paper that sits in a bank vault. Most likely you will never see it. It may or may not have an Intrinsic Value; what it is worth on any given day depends on the confluence of buyers and sellers that day. The most important thing to realize is simplistic: The stock doesn’t know you own it. All those marvelous things, or those terrible things, that you feel about a stock, or a list of stocks, or an amount of money represented by a list of stocks, all of these things are unreciprocated by the stock or the group of stocks. You can be in love if you want to, but that piece of paper doesn’t love you, and unreciprocated love can turn into masochism, narcissism, or, even worse, market losses and unreciprocated hate.