By the end of the 1980s several blue chip companies were worth less than the amount they spent on R&D and capex.

General Motors spent $67.2 billion on R&D and cap-ex in the 1980s and was worth just $26.2 billion by the end of the decade. “Look how much money these companies are wasting on failed projects. They should have returned that cash to shareholders!”

Substitute failed projects with buybacks and you have a pretty good idea where this is going.

The problem with these debates is that minds are already made up. Numbers don’t talk to us, stories do.

With that said, I’m going to provide some data that I think is pretty compelling, but before that, let’s get back to basics with some first principles.

Companies can do three things with cash:

-Sit on it

-Invest it in future projects

-Return it to shareholders

Few companies outside of Berkshire Hathaway have a base of investors that would tolerate giant piles of cash sitting idly around. Investors expect that companies have better uses of capital than letting it pile up in a bank and therefore they entrust management to focus on two things: returning money to shareholders via buybacks and dividends, and investing it in future projects.

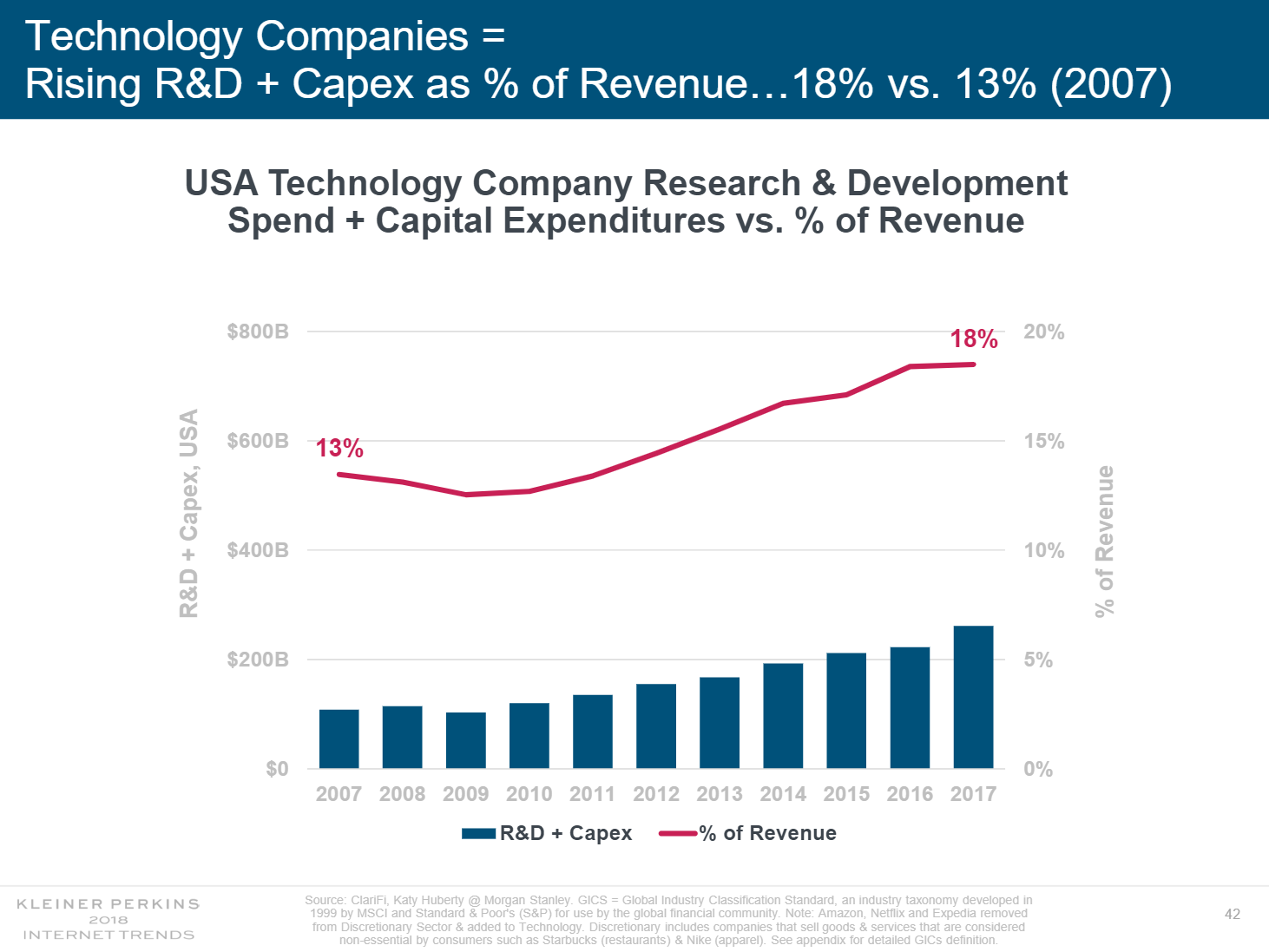

There is this idea that companies are wasting all of their money on buybacks. This just isn’t true. Tech companies spent $52 billion on buybacks in the fourth quarter, more than any other sector. But they’re not buying back stock instead of investing for the future, they’re doing both. In 2017 they spent more than $200 billion on R&D and capex and you can see that the amount they’re spending as a percent of their overall revenue has been rising for the last decade.

Some people assume that management decides to do buybacks to boost the stock price so that greedy executives who are compensated in stock will get the highest compensation possible. I agree that executive pay is out of control, but this is a separate issue. What’s germane to this topic is that these companies should instead be putting the money to work and investing in new ideas. The data does not support this.

In a post from Jack Vogel, Stock Buybacks are Bad? What About the Alternative — Investment, they compare companies with high levels of R&D and capex versus companies that don’t invest heavily in new projects. Jack looks at two different papers and they both come to the same conclusion:

Firms with higher asset growth rates subsequently experience lower stock returns in international equity markets, consistent with the U.S. evidence.

Companies who aggressively “put money to work” often have little or nothing to show for it. Like I said earlier, there exists an alternate universe where companies are just lighting money on fire and investors start screaming, “Look how much money these companies are wasting on failed projects. They should have returned that cash to shareholders!”

Instead we’re living in a world where buybacks are at the root of so many of our problems. The company that has recently been in the cross-hairs of this debate is IBM.

IBM has effectively been dead money for the last decade. They’re up 20%, including dividends, versus 315% for the tech index (XLK). IBM currently has a market cap of ~$100 billion, so when people hear they spent $45 billion on buybacks while their share price went down 38%, people get angry. I get it, it’s an easy argument to make.

But a better argument, which Jake made recently is that poorly managed companies like IBM are doing the right thing by returning cash to shareholders. That’s $45 billion into the hands of investors who can then take that money and actually invest it in companies that are, you know, not terrible. Would the anti-buyback crowd be happier if IBM invested that $45 billion and had a negative ROI? And what about the $76 billion they “wasted” on dividends? Why does this return of capital to shareholders escape criticism? More on this in a minute.

Buybacks and dividends don’t make or break a business. Sure some companies are better capital allocators than others, but we shouldn’t cherry pick to make our arguments. Instead, we should look at the weight of the evidence.

For example, over the last five years, Apple has repurchased $243 billion of stock and still managed to add $456 billion of market cap over the same time. Should we use Apple as an example of why companies should buyback as much stock as possible? Of course not. Apple is a great business because it’s a great business, not because of how they choose to return cash to shareholders.

People are mad and I understand why buybacks are an easy target. They appeal to all of our negativity instincts. Like I said earlier, minds are already made up, numbers won’t change anything.

While buybacks have been the center of the CEO pay/income inequality debate, I suspect that dividends are going to start getting a lot more attention, especially if people start talking about how companies are favoring shareholders over employees. For example, Disney stopped paying 100,000 workers to save $500 million a month, and yet they’re still planning on doling out a $1.5 billion dividend in July. If we start hearing more stories like this, things could get ugly in a hurry. A battle between the working class versus the investor class is not something anyone hopes to see.

*data from Jack Vogel’s post