As the 20th century was coming to a close, the dominant retailer J.C. Penney had a market capitalization of $20 billion. Today it’s down to $60 million and with $4 billion in debt coming due, they’re on the brink of bankruptcy.

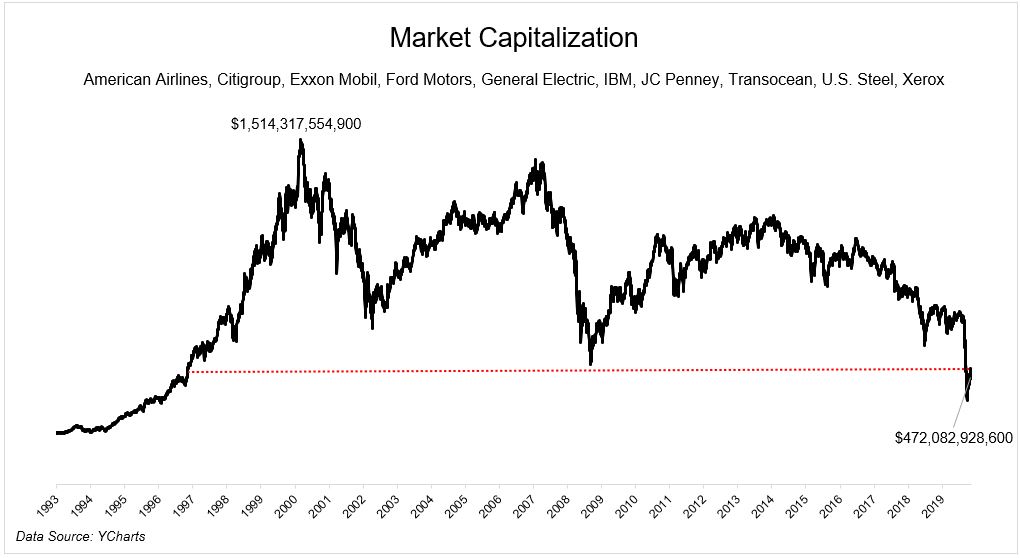

During the 1990s, JCP, along with American Airlines, Citigroup, Exxon Mobil, Ford Motors, General Electric, IBM, Transocean, U.S. Steel, and Xerox were among the bluest of blue chips. These brands were global icons and were beacons of American ingenuity. At the peak of their powers, they were worth a collective $1.5 trillion, or 12% of the S&P 500.

But the world ground gradually shifted beneath their feet. Over time SUVs replaced sedans, email replaced the fax machine, and the internet replaced the department store. These 10 companies fell 70% from their peak, shedding over a trillion dollars in market cap in the process. Their value is unchanged since 1997.

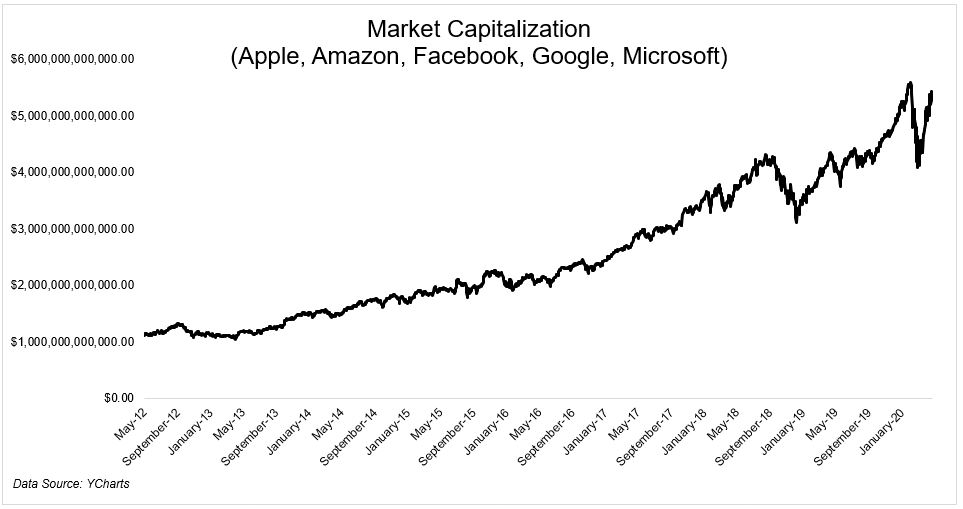

Today’s blue chips dominate not just our portfolio, but our every waking moment. Unlike the companies above, Apple, Amazon, Facebook, Google, and Microsoft are each a part of our daily lives. It’s hard to imagine a world without them, which is how they managed to grow to $5 trillion. At more than 20% of the S&P 500, they represent the largest share of the index held by the top five companies since the early 1970s.

The other day I wrote that if the growth rate of these companies continues, in 13 years they will be bigger than the S&P 500 itself. If this were to continue, the Department of Justice would have to break these companies up. While possible, I think a more likely outcome is that these kings get dethroned by competition, not governmental interference. Todd Bucholz wrote about this in New Ideas by Dead Economists.

In a remarkable commencement address at Stanford, Steve Jobs recalled dropping out of college on his way to challenging IBM.

“I didn’t have a dorm room, so I slept on the floor in friends rooms. I returned coke bottles for the five-cent deposits to buy food with, and I would walk the seven miles across town every Sunday night to get one good meal a week at the Hare Krishna temple. I loved it. And much of what I stumbled into by following my curiosity and intuition turned out to be priceless later on.”

For more than thirty years, the Justice Department was attacking IBM. But it took a dropout like Steve Jobs, not starchy antitrust lawyers, to create more intense competition.

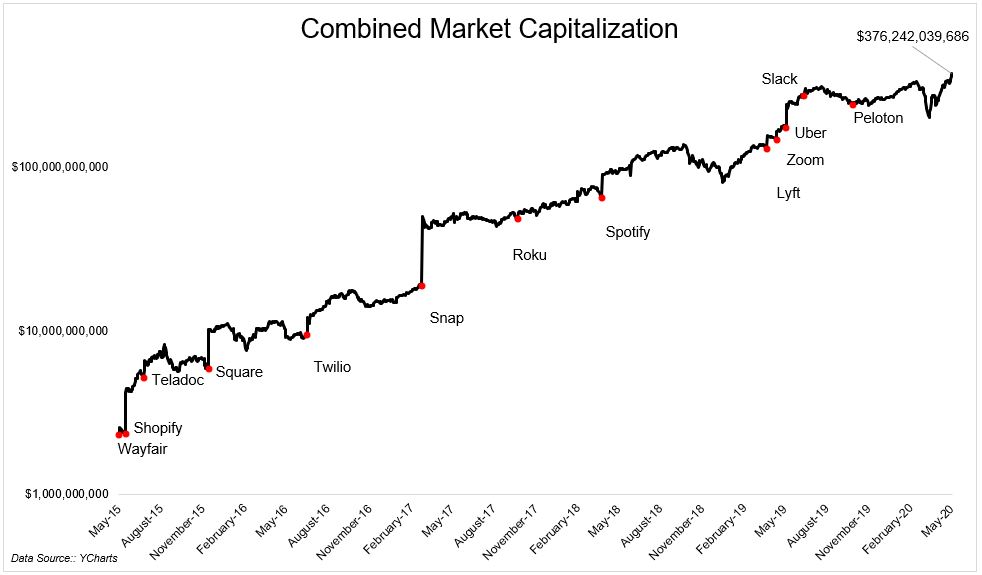

Over the last few years, as the big tech companies became goliaths, a new swath of companies were busy building. Wayfair, Shopify, Teladoc, Twilio, Snap, Roku, Spotify, Lyft, Zoom, Uber, Slack, Square, and Peloton collectively added $343 billion in market cap to the public markets ($203B or 54% of the current value, was added post-IPO).

It’s really hard to see a future where Amazon loses power, but that could have been said about each and every one of the great companies of the past. Right now Peloton is “just” a company that sells bicycles and treadmills, but in 1997, Amazon was “just” a company that sold books online. Maybe it truly is different this time, that the next Amazon is Amazon, but history suggests this isn’t something worth betting the farm on.

The rise and the fall is the business equivalent of the circle of life. The old and stodgy are replaced by the young and hungry. This is not merely a feature of the most dynamic wealth-creating machine ever, it’s the engine that drives it.