I recently listened to Netflix Versus Blockbuster on Business Wars. The whole series is fantastic, and I wanted to highlight three moments in time that stood out to me.

In 2007, Blockbuster brought in a new CEO, Jim Keyes. He said to Shane Evangelist, Senior VP and GM of Blockbuster Online:

The online business is killing Blockbuster. You spent $450 million marketing total access and you’re way over-budget. I’m cutting off your marketing budget so we can focus on the stores.

David Brown, host of the podcast, said,

Keyes was suggesting essentially killing the online part of the business, the one thing Blockbuster was finally getting right. Defying reason, Keyes wanted to return to the days of video rental stores…By seeking to end the bleeding in marketing, Keyes had only succeeded in opening an artery. Ultimately it would turn out to be a fatal self-inflicted wound.

Blockbuster had an online service called Total Access where you could rent DVDs on the internet and return them to the store. It was catching on with customers and Netflix was losing subscribers as a result. Shane Evangelist reminded Keyes that Netflix offered to pay Blockbuster $200 per subscriber and that they should revisit that offer. Inexplicably, Keyes wouldn’t listen. Three years later, Blockbuster filed for bankruptcy

You probably remember how lousy Netflix’s streaming catalog was early on. When they launched in 2007, there were only 1,000 titles, which was just 1% of what they offered through their mailing service. By the following year that number jumped to 10,000. The library was growing but the quality wasn’t. I remember in 2010 thinking that Netflix was a short for exactly this reason. ¯\_(ツ)_/¯. The internet was abuzz with negative feedback about the streaming service, but Reed Hastings didn’t care. He wasn’t focusing on that. Here’s David Brown:

Reed Hastings isn’t really bothered by the chat storm, I mean at least it shows customers are trying the streaming app. But you know that expression content is king, well it turns out sometimes it isn’t. Sometimes it’s a hard-working algorithm that burrows into customers habits. See, it’s not just viewers watching Netflix here, it’s the Netflix algorithm watching the watchers. It sees not only how people search for movies, but how long they watch them, even if they say they don’t like them.

I learned a very important lesson from my multiple failed attempts to short Netflix’s stock. A lesson so simple that I’m actually embarrassed to type this; things change. I thought the streaming service was rotting when in reality it was building. Netflix would soon land a contact with Starz that gave it access to Sony and Disney movies. But Netflix knew that it wasn’t going to be able to rely on outside studios forever. They needed to get into the content creation business. So in 2013, they paid $100 million, a large chunk of of their budget at the time, to distribute House of Cards. How did the world react? Here’s David Brown:

The entertainment industry is buzzing with predictions of disaster. Sarandos is a fool to release all the episodes at once. People will run out of shows to watch and cancel their service if they can watch all they want. The shows won’t resonate if viewers can watch them all at once the critics say. And what did Netflix know about making television anyway?

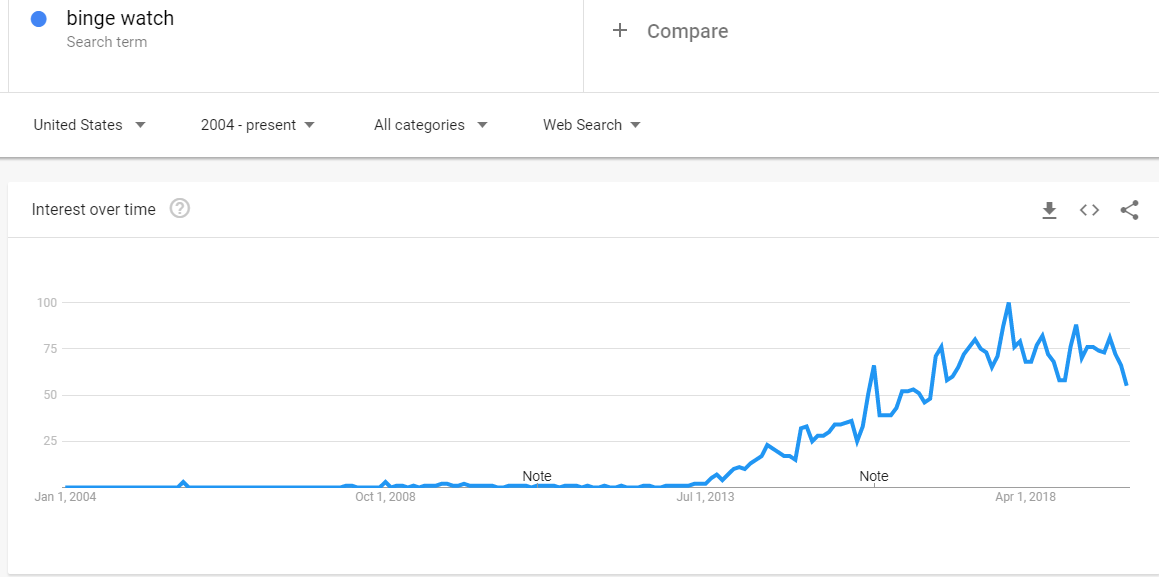

Since House of Cards dropped, they’ve delivered hit after hit: Orange Is the New Black, Stranger Things, The Crown, Ozark, Narcos, Making a Murderer, and Mindhunter, to name a few. It’s hard to believe that “binge watching” is only six years old.

The winners always appear pre-destined in hindsight, but a lot of things had to go right for Netflix to end up with 150 million subscribers, and you can learn all about it in this excellent podcast.

Time Warner Views Netflix as a Fading Star (December 2010)

Former CEO Jim Keyes: Why Blockbuster Really Died and What We Can Learn from It