You cannot be online and think things are getting better. Let me show you one example.

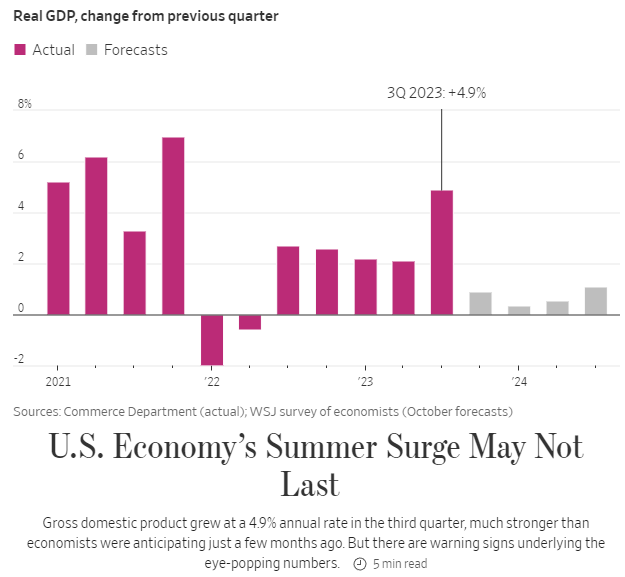

This was on the front page of The Wall Street Journal yesterday.

Instead of a headline like “U.S. Economy Grows at Fastest Pace in Two Years,” they wrote:

“U.S. Economy’s Summer Surge May Not Last”

And below it, “There are warning signs underlying the eye-popping numbers.”

Charlie Munger once said, “Show me the incentive and I will show you the outcome.” We all understand what’s going on here. The media is in the business of generating dollars. And a large part of the dollars they generate are from advertisers. So their incentive is not necessarily to lie or mislead you, it’s to make you feel something so that you click on the link. And negative feelings are much more likely to generate clicks than positive ones.

Nobody watches the weather channel when it’s 70 and sunny.

News and social media are a drag on happiness. If I had to describe the economy using one word, I would use “strong.” If I had to describe the consumer in one word I would use “anxious.”

This is a dramatic oversimplification of extraordinarily complex topics, but I use those words to show the dichotomy between how things actually are versus how people feel.

And the gap between these two camps is widest among those who are online and consume the news and those who do not.

In Morgan Housel’s new and incredible book, Same as Ever, he writes about how we got to now.

Information was harder to disseminate over distances, and what was going on in other parts of the country or the world just wasn’t your top concern; information was local because life was local.

Radio changed that in a big way. It connected people to a common source of information.

TV did it even more.

The internet took it to the next level.

Social media blew it up by orders of magnitude.

Digital news has by and large killed local newspapers and made information global. Eighteen hundred U.S. print media outlets disappeard between 2004 and 2017.

The decline of local news has all kinds of implications. One that doesn’t get much attention is that the wider the news becomes the more likely it is to be pessimistic.

Two things make that so:

- Bad news gets more attention than good news because pessismism is seductive and feels more urgent than optimism.

- The odds of a bad news story- a fraud, a corruption, a disaster- occuring in your local town at any given moment is low. When you expand your attention nationally, the odds increase. When they expand globally, the odds of something terrible happening in any given moment atr 100 percent.

To exxagerate only a little: Local news reports on softball tournaments. Global news reports on genocides.

A researcher once ranked the sentiment of news over time and found that media outlets all over the world have become steadily moire gloomy over the last sixty years.

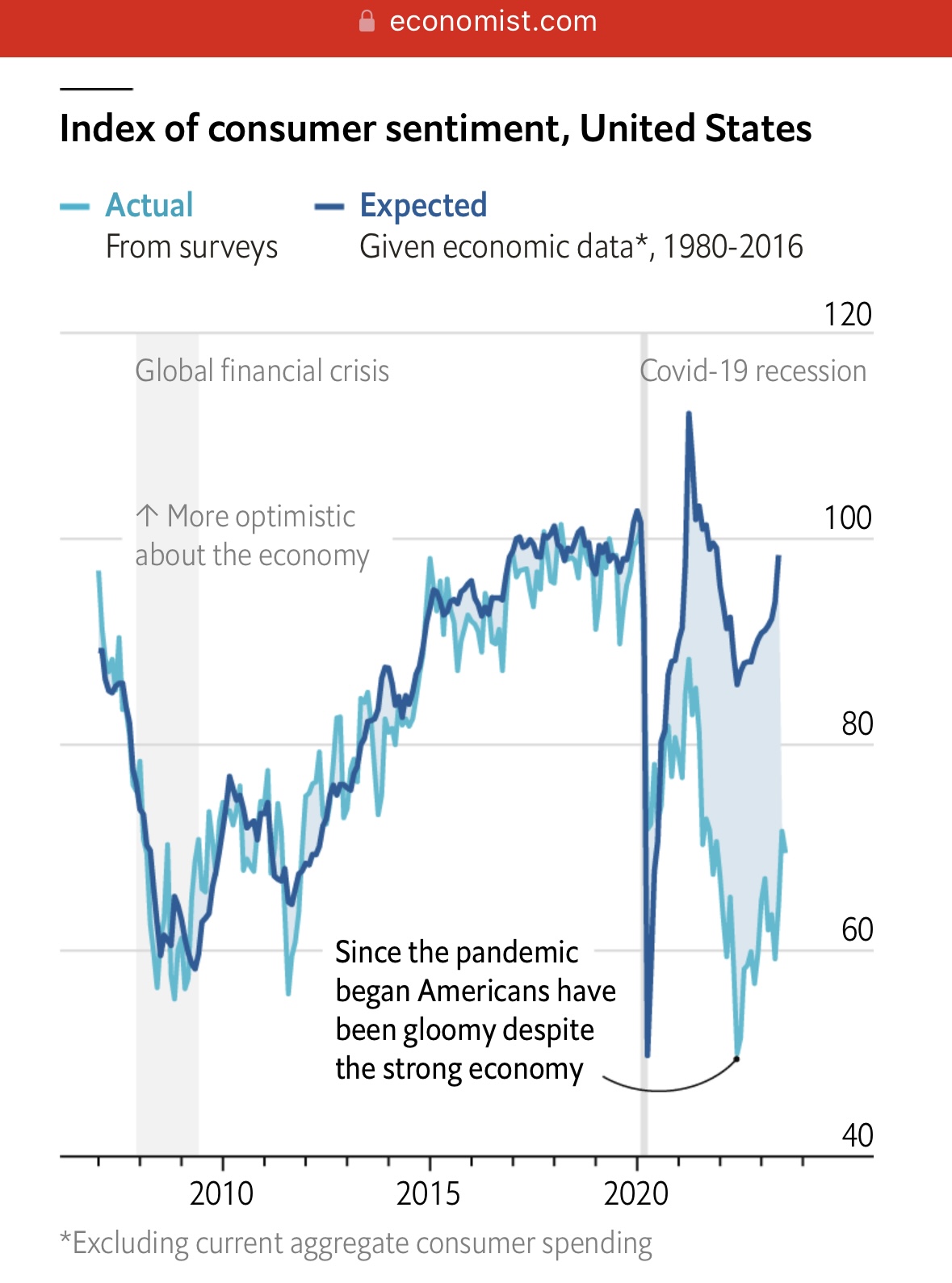

This is one of the more important changes in our society over the last couple of decades, and certainly it’s not all due to the media, both social and traditional. Prior to covid, people’s moods generally reflected the state of the economy. They were optimistic when times were good and pessimistic when times were bad. Covid took this relationship and tore it into a thousand little pieces.

We were all forced to drink a nasty cocktail of being locked in our homes for a year mixed with rapidly rising prices and a garnish of interest rates not seen in decades. And now we’re battling a long and intense hangover. As the economy continues to chug along, hopefully it’s the light blue line that catches up to the dark blue line, and not the other way around.